I love borrowing audiobook CDs from the library to listen to in the car with my son. The last one we listened to was Carry On, Mr. Bowditch by Jean Lee Latham. It’s a fascinating novelization of the true story of Nathaniel Bowditch, who was forced to leave school and become an indentured servant at the age of 10. Despite this, he taught himself mathematics and multiple languages and revolutionized navigation by publishing The New American Practical Navigator in 1802. Remarkably, this guide is still published and used aboard ships, with the latest edition released in 2019! Carry On, Mr. Bowditch is a story of resilience and determination, and I hope my son absorbed some character traits from it that will help him grow into a successful and hard working man insha Allah. However, there was one part of the book I found troubling—Chapter 4, titled “Boys Don’t Blubber.”

In that chapter, Nathaniel (Nat) returns home from school to find his elder brother, Hab, who has signed up to join the crew of the ship Freedom. Nat is very close to Hab and admires him deeply. The following exchange then takes place:

Nat remembered last winter when Hab had outgrown his coat. “Did you get cold last winter, Hab?”

“Plenty cold.”

Nat was puzzled. “But when the boys yelled at you, you always said, ‘I’m not cold. Only sissies need winter coats.’”

“Of course.” Hab frowned. “Boys don’t blubber. If something hurts, you say it doesn’t.” He looked up at the tall masts of the Freedom and grinned. “She’s a grand ship, isn’t she?”

Nat’s stomach felt hollow. What would it be like with Hab gone? But boys don’t blubber. He bit his lips to steady them and squared his shoulders. “Yes, Hab. A grand ship. How — how — long before you sail?”

Nat carries the phrase “Boys don’t blubber” throughout the story, suppressing his emotions as he endures significant challenges, including the loss of multiple loved ones. As Tasniya described in her post last week, we provide our son a safe space to feel, and express, his emotions, which we believe is essential for his healthy emotional development.

It’s not easy to see our children cry. Many of us instinctively want to stop the crying as quickly as possible—by giving in to their demands, distracting them, or coercing them into silence. Reflecting on your own childhood, how were you treated when you cried? Many of us were likely told to stop crying or not to cry at all. I remember being told not to cry, which taught me, at a very young age, to bottle up my emotions. If you had a similar upbringing, seeing your child cry can trigger discomfort and even fears that your child might be perceived as weak.

For fathers especially, seeing their son cry can feel challenging if they were pressured to “toughen up” as boys. This can lead to unconscious parenting patterns that mirror how we were raised. However, as I suggested in my last post, practicing mindfulness can help us notice and adjust these patterns before acting on them.

Crying is an essential means of communication for babies and toddlers who cannot yet express their needs verbally. Responding to their cries teaches them to trust their caregivers and builds a strong attachment relationship, which is a foundation for successful parenting. In future posts, we’ll explore the importance of attachment and why we believe it to be the envelope within which all other parenting approaches should be adopted.

As children grow and develop language, crying continues to serve an important role in emotional regulation. As discussed in Hold On to Your Kids (our next book club selection), bringing children to futility—helping them accept situations where they cannot get what they want—is crucial for emotional growth. A key part of this process often involves crying, which allows children to let go and move forward.

My wife has pointed out my own struggles with emotional expression. The phenomenon of toxic masculinity—promoting stoicism and suppressing emotions—often feels like the cumulative result of generations of boys raised to “man up” and bury their feelings. Brené Brown’s concept of emotional armor provides valuable insight here. Children often suppress their emotions around peers to avoid being teased or bullied. This isn’t harmful if they can remove their armor in the safety of their home. However, if they lack a safe space to express vulnerability, they risk becoming hardened and disconnected from their emotions. As Brown describes, fostering a balance of strength and openness can help children develop what she calls a “strong back and soft front.”

“All too often our so-called strength comes from fear, not love; instead of having a strong back, many of us have a defended front shielding a weak spine. In other words, we walk around brittle and defensive, trying to conceal our lack of confidence. If we strengthen our backs, metaphorically speaking, and develop a spine that’s flexible but sturdy, then we can risk having a front that’s soft and open, representing choiceless compassion. The place in your body where these two meet—strong back and soft front—is the brave, tender ground in which to root our caring deeply.”

As a Muslim, I often turn to Islam for guidance, and on the subject of crying, there is ample evidence that it is not only permissible but praiseworthy when done for the sake of Allah. The Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) himself cried on many occasions, both during worship and in response to personal loss. In one instance, the Prophet (ﷺ) spent the whole night crying while reflecting on a single verse of the Quran:

…Ibn Umayr said (to Aishah):

Tell us about the most interesting (or “amazing”) thing you have seen from the Messenger of Allah ﷺ. He said, she remained silent and then said: “On one night, the Messenger (ﷺ) said to me: “O Aishah, excuse me to worship my Lord on this night. I (Aishah) said: “By Allah, I love your companionship and I love what makes you happy. She said, he (the messenger ﷺ) stood and purified himself, then stood in prayer. She said he began crying until his cheeks became wet, and (she said) he cried after that until his beard was wet, and (she said) he continued crying until the tears started to fall to the ground. At that moment, Bilāl (Radiallahu Anna) came to the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) to announce the Fajr prayer and he saw him crying. He said, “O Messenger of Allah, why are you crying? Indeed, Allah has forgiven your previous and future sins.” The Messenger replied, “Shall I not be a grateful servant? A verse has been revealed to me on this night, woe to the one who reads it and does not reflect upon it. He then read: “Verily! In the creation of the heavens and the earth, and in the alternation of night and day, there are indeed signs for men of understanding” (3:190).”

[Sahih Ibn Hibban]

In another instance, the Prophet (ﷺ) cried over the death of his son, Ibrahim:

Narrated Anas bin Malik:

We went with Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) to the blacksmith Abu Saif, and he was the husband of the wet-nurse of Ibrahim (the son of the Prophet). Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) took Ibrahim and kissed him and smelled him and later we entered Abu Saif's house and at that time Ibrahim was in his last breaths, and the eyes of Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) started shedding tears. `Abdur Rahman bin `Auf said, "O Allah's Apostle, even you are weeping!" He said, "O Ibn `Auf, this is mercy." Then he wept more and said, "The eyes are shedding tears and the heart is grieved, and we will not say except what pleases our Lord, O Ibrahim ! Indeed we are grieved by your separation."

[Sahih Al-Bukhari]

In addition to his own examples, the Prophet (ﷺ) emphasized the virtues of crying for Allah’s sake.

It was narrated from Abu Hurairah that the Prophet (ﷺ) said:

"No man will enter the Fire who weeps for fear of Allah, Most High, until the milk goes back into the udders. And the dust (of Jihad) in the cause of Allah, and the smoke of Hell will never be combined."

[Sunan an-Nasa'i]

By discouraging behaviors like crying, we risk stunting our children’s emotional growth. Instead, we should teach them to recognize, understand, and process their emotions productively. While this post focused on crying, the same approach applies to other emotions like anger, frustration, and shame. Insha’Allah, in future posts I plan to delve into methods to cultivate emotional intelligence and resilience, but I’ll leave you with this excerpt from Brené Brown’s Wholehearted Parenting Manifesto:

“Together we will cry and face fear and grief. I will want to take away your pain, but instead I will sit with you and teach you how to feel it.”

I hope you found this post helpful. Please share your thoughts or feedback in the comments.

Until next time, here are a few reflection prompts:

Think about the last time your child showed strong emotions. How did you handle it? Would you do anything differently?

Reflect on a painful childhood memory. How did you feel? Were you supported, or did you feel alone?

Read Brené Brown’s Wholehearted Parenting Manifesto and share your reflections on the Fob Chat.

As you know, we offer monthly group coaching sessions through Fob Village. If you’d like to be part of this incredible community of parents, I highly encourage you to join us! You’ll gain valuable parenting tools and skills to help you show up as a more confident parent and leader for your child, inshaAllah.

Check out some of the testimonials from members of the Fob Village! We can’t wait to welcome you into our community so we can grow together through our monthly group coaching sessions, inshaAllah!

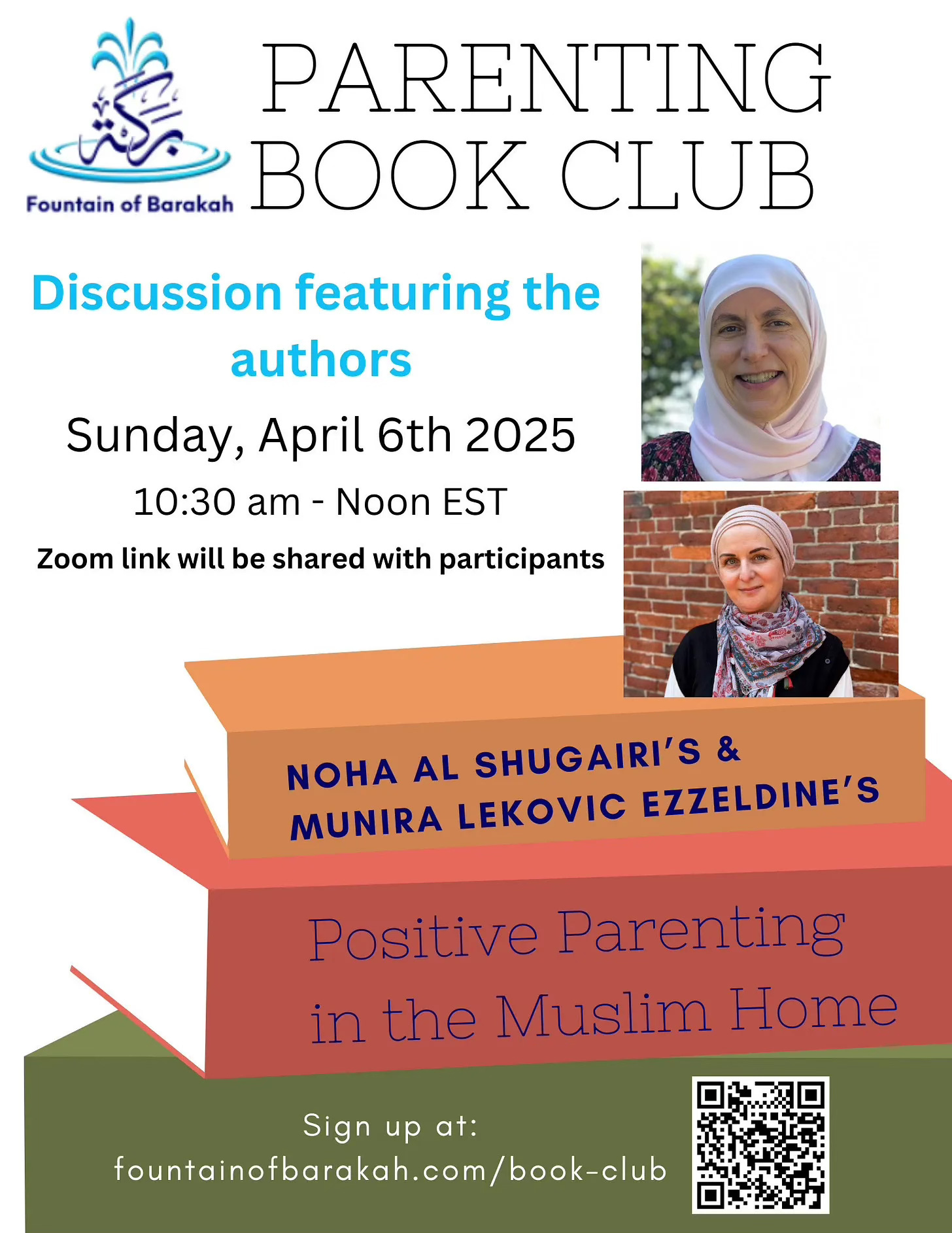

We’re excited to announce that both authors of the book Positive Parenting in the Muslim Home will be joining our book club discussion in April! This is a fantastic opportunity to have your parenting questions answered directly by the authors. We’re personally looking forward to this discussion session and can’t wait to learn from these experts in the field of positive parenting, inshaAllah!

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.